Yesterday’s International Holocaust Memorial Day commemorated the anniversary of the Soviet liberation of Auschwitz. For Jews, especially those with European heritage, Auschwitz is synonymous with the Holocaust. Located in Poland, it was the largest of the camps and Jews from all across Nazi-controlled Europe were brought here. Almost one million Jewish men, women and children (approximately 90% of the camp’s victims) were murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

But how did the site of one of the worst atrocities on Earth become a museum? How did people who looked the other way during the War change to building the most powerful Holocaust remembrance in the world?

The answer is – they didn’t.

Today we tell the story of Tadeusz Wąsowicz, a Catholic resistance fighter who dedicated his life after WWII to the concept that the world should never forget the Nazi atrocities against the Polish people. But as a former inmate of Auschwitz, he resisted converting the camp into a typical museum of the time and built a culture of letting the buildings, artifacts and graveyards stay intact (or be restored as much as possible) to tell the story.

Thank you to Board Member Hal Schild for his inspiration and research on this story!

– Marnie Fienberg, Editor

_____________________________________________

The Soviets were not known for their humanist works, yet the Auschwitz-Birkenau museum was founded by the Soviet-controlled Polish government. Liberating the camp in January 1945 had a profound effect on the Soviet and Polish soldiers and they would never forget it.

One man dedicated his life to the belief that the horrors he had experienced should be remembered as they happened. Tadeusz Wąsowicz, a Catholic former inmate at Auschwitz-Birkenau, rallied the Polish government and gathered other former Auschwitz-Birkenau prisoners to convert Auschwitz-Birkenau from a place of death to a place of learning, remembrance and respect for the victims.

One man dedicated his life to the belief that the horrors he had experienced should be remembered as they happened. Tadeusz Wąsowicz, a Catholic former inmate at Auschwitz-Birkenau, rallied the Polish government and gathered other former Auschwitz-Birkenau prisoners to convert Auschwitz-Birkenau from a place of death to a place of learning, remembrance and respect for the victims.

Wąsowicz was a respected Polish historian and scientist. In 1938, he joined the Polish army and became a leader in the Resistance, called the Gray Ranks, after Poland fell to the Nazis. When the Gray Ranks was betrayed by one of their members in 1941, he was captured and beaten but refused to betray any of his fellow resistance fighters. He was sent to Auschwitz as a political prisoner. Wąsowicz’s brother was murdered at Auschwitz that same year.

Wasowicz was selected to fill in the registration sheets of prisoners arriving at the camp and maintain statistics of their status, making him aware of the overall layout and multiple purposes of the complex, who lived and who was killed. He worked to help make life bearable in the camp as much as he could, co-organizing an underground scout fighting group codenamed “Droga Brzozowa.” The group smuggled in food and medicines, prepared and passed on lists of prisoners and information outside the camp, and organized cultural life, including lectures and performances.

Auschwitz was split into multiple sections that grew over time, later to include the Birkenau section which was focused on extermination. Almost one million Jews were killed, but it was not exclusively a death camp for Jews. Approximately 75,000 Polish civilians, 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war, 25,000 Roma and Sinti, as well as Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals and political prisoners were put to death by the Nazi state at the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex. Wasowicz spoke about what he saw in his testimony later at the Polish Auschwitz Trial in 1947.

As the Soviets advanced on Auschwitz, the Nazis began evacuating prisoners to other camps, most on foot (known as the Death March), closer to the Western Front and destroying evidence of what they had done. On December 12, 1944, Wasowicz was transferred to Gross-Rosen, and on January 23, 1945 to Buchenwald.

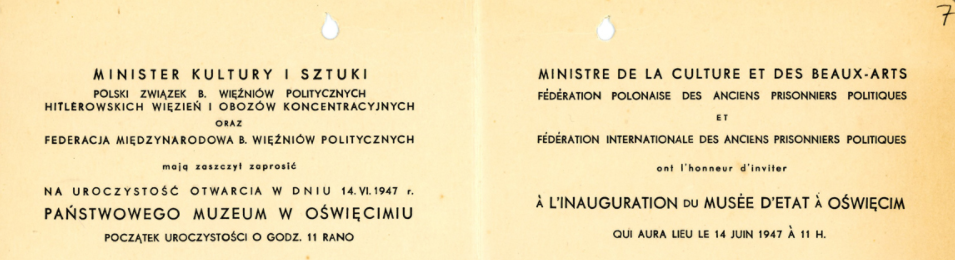

The opening of the Auschwitz camp museum. Director Wąsowicz is on the right.

Founding the Auschwitz – Birkenau Museum

He was liberated on April 11,1945 by the Americans and returned to Poland as soon as possible on August 14, 1945. Working for the Polish Red Cross, Wasowicz supplied them with much of the data he had managed as a prisoner. This information provided a critical list of missing people and showed that they had been murdered by the Nazis.

In 1946 he helped lead an organization of former prisoners to secure the area of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp and commemorate its victims and establish the first Auschwitz-Birkenau museum. Wasowicz and other survivors worked in partnership with Poland’s Ministry of Culture and Art and a law was passed in 1947 to formally establish the museum and funding. This partnership was critical to setting the tone of the museum – what was saved, displayed and discussed told a specific story about the horrors that befell the Polish people. As survivors, Wasowicz and his team had a first-hand memory of their experience and they wanted to tell the story. Wasowicz was adamant that the museum should maintain the camp in accordance with its actual state as much as possible. This was an unpopular approach to museums at the time, but resonated with visitors.

Many of the structures, including the blocks in the main camp, and the brick blocks, guard towers, main gate, and some of the wooden barracks were still in relatively good condition. Although the Nazis destroyed records and personal items in the last days of the war, many items of various kinds that had belonged to the murdered Jews were found and included in the Museum exhibits over time.

The team prepared an exhibition and routes for visitors, and began showing guests around the site. In these early days, the Polish side of the story was the main focus of the story. Wąsowicz’s team also collected and secured all material evidence of crimes, objects of historical value, and sent those documents to the District Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Krakow.

Director Wąsowicz made a point of hiring former (probably non-Jewish) inmates of Auschwitz as guards, docents/guides, bringing the staff of the museum from four in 1946 to more than 50 in 1947. These men served with a passion for their work, knowing that they were building something critical.

The Birkenau section of the camp where the majority of the Jews were slaughtered and worked to death was controversial, partially because the Polish leaders at the time felt the horrors were too much for the average visitor to imagine. Over time, starting in the late 1950s, with the founding of the Jewish state of Israel and the rise of Holocaust scholars, the full story of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp began to emerge. We will tell this story in a future article.

Tadeusz Wąsowicz died on November 26, 1952 from complications from an overactive thyroid and was buried in the family tomb in the Rakowicki Cemetery in Krakow.

From 1955 to 1990, the museum was directed by one of Wasowictz’s colleagues, Kazimierz Smoleń who continued Wąsowicz’s vision to let the buildings tell the story. More than 45 million people across the world have visited the museum, and the Auschwitz memorial was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979.

What Might Have Happened Without Wasowicz?

Wąsowicz was not focusing on fighting anti-Semitism, but rather with telling the story of Nazi atrocities. Yet, without his open air museum approach, Auschwitz may have been a small, “under glass” style gallery with most of the original buildings plowed under for much needed farming. If this had happened, later Holocaust scholars would have had the nearly impossible task of recreating the camp under a Soviet regime. We have Wasowicz and his colleagues to thank for creating a foundation where the full truth could eventually be told. Good actions can set the stage for more good actions.

For further Reading

![]() Auschwitz, Poland, and the Politics of Commemoration,1945-1979 by Jonathan Huener, 2003

Auschwitz, Poland, and the Politics of Commemoration,1945-1979 by Jonathan Huener, 2003

Read more about the first years of the Museum

Read more about Auschwitz employees reminiscing about the founding of the Museum

Wąsowicz’s testimony of what happened at the Auschwitz camp

_________________________________________________